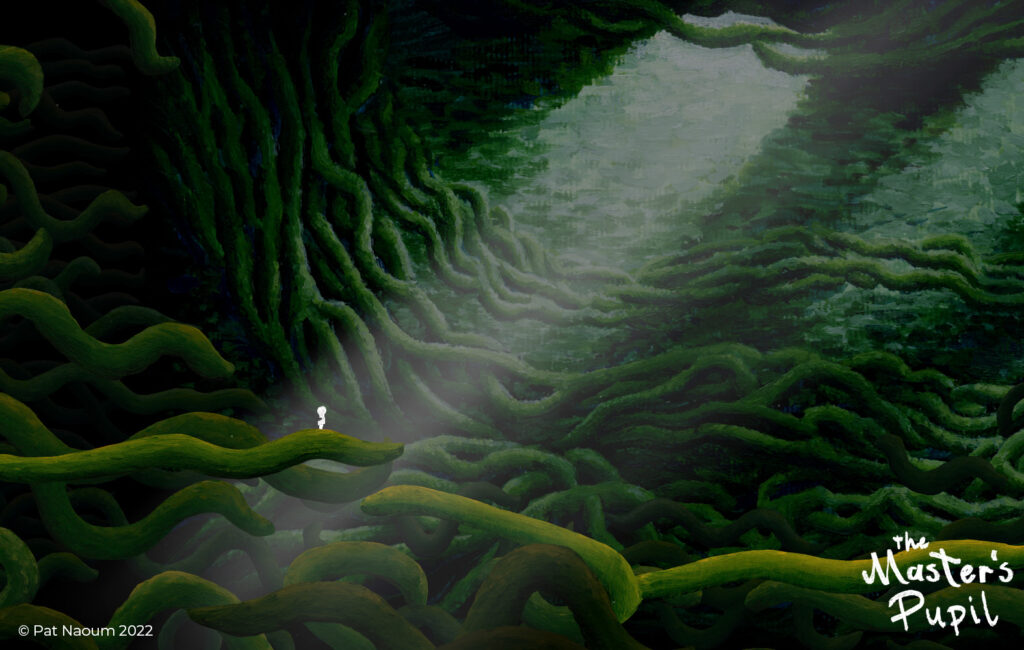

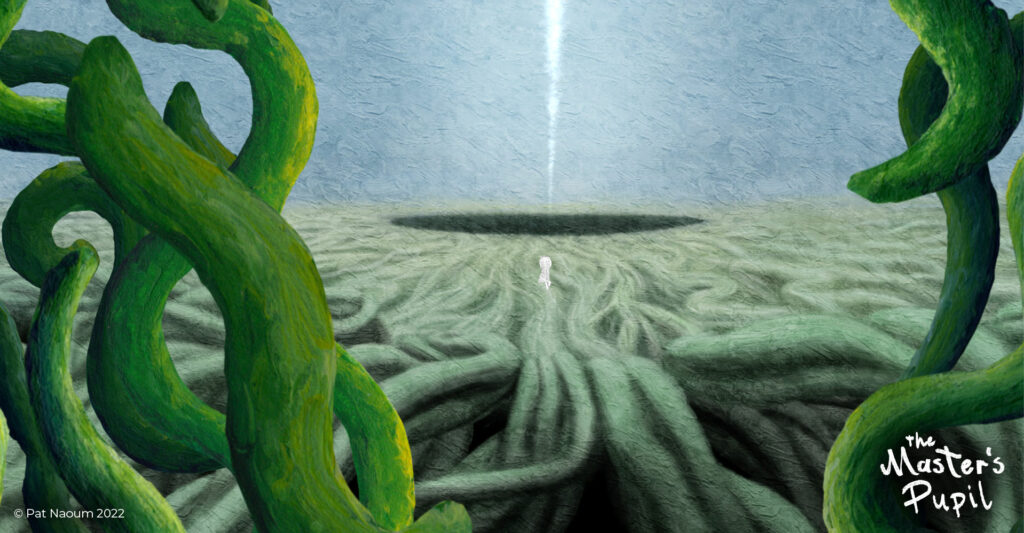

The Master’s Pupil is a hand painted puzzle-adventure story set in the eye of 19th century impressionist painter Claude Monet. You journey through the many challenges and difficulties he faced in his life through surreal landscapes and sights.

We were recently fortunate enough to be working with Pat to port the game to Switch, in addition to sitting down to chat about it more! Hear more about his own journey into game development, as well as some interesting insights into the game. Enjoy!

Could you share how you got into solo game development? What were some highlights you experienced?

I came from a fairly unusual path, because I came out of high school wanting to do visual art. I studied a Bachelor of Visual Art and majored in painting, minoring in Media Arts. This was an elective where I tried to do some programming and failed miserably. Well, my whole class failed miserably and they had to have us redo our final exams so we would not. It was a bunch of artists doing programming and the majority of the class still failed.

That was where I made my First Game. It was a text based game that spat words at you, letting players experience something like a strange little book, with decisions you could make. It was the most basic point and click adventure game you could ever experience, yet it was such a struggle for me to make.

Then, I went into film school (Australian Film Television Radio School), because I wanted to experience film industry roles and try to become a director making my own shorts. In addition to this, I also fell into graphic design. So, I was doing graphic design freelancing whilst also working in the film industry.

At some point however, I was bumping my head against the idea of working in the film industry. Because, if you want to be a director, the path to being a director is having to do a bunch of short films or ads or music videos. Your first year or two is mostly crossing your fingers, writing something, and then trying to get stuff made once or twice a year, actually filmmaking for a weekend. If it rains, then your short film is stuffed up. Or, if an actor gets sick, your music video can’t work.

What I realised was that I was after something that was much more like daily practice… like making a game or artwork slowly and doing it every day.

Part of what was exciting about game development was that I could just boot up my computer, open up Unity and start fiddling. I could do that everyday for half an hour or 8 hours, with nothing stopping me. I didn’t have to hire equipment to be able to shoot something or rely on other people and their timelines to be able to make a short film or music video. I could make a story and plot away at it really slowly. That was exciting, and also convenient!

Games also include everything from writing to music to art to 3D sculpture, to sound design and acting— they could be a mashup of all these different types of mediums that create a whole.

Finally, unlike film, someone can play it. Every other artform is mostly people looking at it and going: “Mmm. Great. Thank you.” For games, you deep dive into it. So, yeah, it’s a fun medium to be in really!

Being the only person in charge of all of that, surely there were some difficulties that you experienced. What were some of them?

Yeah, well. Painting a game is tough. Plus, solo gamedev means everything is on your shoulders, including if you’re making the right game or whether what you’re doing is right. You have to talk yourself into it.

There were also thousands of little problems I had to solve because I was the only one making this! I didn’t know how to code, so problem solving involved literally downloading the yellow C# explainer book. I thought: “Well, at school I knew how to study things. So I can study this book with notes and stuff.”

My first prototypes were just downloading little snippets of code, sticking them together and smooshing them in, trying to make it work. I think this building process is really fun because if a problem comes up, you just have to keep pushing through it and it really makes you a better coder or better game designer because there’s no one else to fill in the gaps. You just have to do it.

You spent years making The Master’s Pupil. How did you stay motivated throughout?

I was looking up my old notes and found that the idea of a game set inside an eyeball was from ten years ago. Since then, it has slowly morphed into what it is now. This game and some of these assets, like the main character’s run cycle, are seven years old. It’s a really strange process to be working on this game really, really slowly. But I enjoy chipping away at a large project everyday, it’s almost a source of motivation for me.

This is my first game, it’s not that huge, but it’s still way bigger than a first project ought to be. All the advice online tells you to “Make something small. Make a really small prototype that’s really fun and get it to a point where it’s playable and downloadable. Put it up for free, do that again three times and then, make your desired first game.”

But I was like: “No way. I’m going to do this, I’m going to make the game that I want to make and dream big.”

I think that motivated me because I wasn’t fiddling around and bashing my head up against problems that were just to make a little free game. I was making a 12 level puzzle game that was intricate and interesting and had developing mechanics that could only work over the course of 5 hours. I wanted to make something big and make it good. The continuous progress and routine was motivation.

Initially, I used any downtime I had to get in a little bit of game development. This eventually resulted in a vertical slice that was polished, and something I could get good feedback from. From there, and this was four years ago, I went down to essentially part time hours, around 3:00PM every day I’d work on a couple of hours. That number eventually started getting further and further until eventually I was working freelance through the day, up until about lunchtime, then switching to game development.

Again, I don’t know if that’s the best way of doing it, but it worked for me. And then getting the Screen Australia Grant enabled me to go full time and actually hire good folks like Noble Steed Games to help with Switch porting and testing. There’s a hurdle at some point that you need to get over with a little help.

What are your plans after The Master’s Pupil?

I know the game that I’m going to make next and I know the game that I’m going to make after that as well! Coming from an art background, it’s something that you’re always thinking about: Your next painting or your next artwork… daydreaming about games you want to make. I’ve got these ridiculous long notes that are just silly ideas I’ve written down.

Once the creative work on a game is done, like in The Master’s Pupil, there’s so much creative free time. I think there’s pre-work that you do when you’re making something, especially when you’re making your first game. It takes so long for it to get made because you’re learning all this other stuff. I think that’s the problem with a lot of people making games, and it’s especially obvious with musicians. Very often a musician will release a mind-blowingly good first album, then they quickly make a second album in a year that’s just okay. They didn’t spend five years making it like their first, so they don’t have enough time to craft it well enough.

Whilst making The Master’s Pupil, I’ve had so much downtime to daydream, spending time to come up with another game. I haven’t done any coding, but I’ve got some conceptual drawings and a document that needs a heavy, heavy edit.

Anyway, it’s a very different game. I think the joke that I’ve been sharing with my mates is that the next game is going to be set in Van Gogh’s ear, so it’ll get cut off in the final! Haha, but no, the next project is going to be a bigger open world survival game, with some procedurally generated stuff that’s very different to TMP. We’ll see what happens when I start diving into it. Maybe I’ll bite off more than I can chew. Hopefully it won’t take seven years, but I hope to keep developing games!

Because it’s awesome, it’s fun! (Pat’s also got a card game in the works!)

Why did you decide to explore impressionism through TMP and why did you want to depict Monet’s life? What drew you to it?

Originally I had this idea of a game set inside an eyeball, where you start on the edge of the iris, and travel towards the pupil. I thought of having the journey end in a dramatic landscape.

This landscape and a journey was what I wanted to fiddle with. There were ideas about exploring macular degeneration in the eye, which my grandfather had, but had nothing to do with the iris.

Then I thought: A cataract sits on top of the iris.

I thought that would be interesting, an endgame where you run across the iris and then into the cataract. It was later that the idea of having the game cover the course of someone’s lifetime came to me. Especially since the cataract develops as you age, and things like surgery and treatment come into your later life.

From art school, I remembered that Monet had cataracts and that Monet was from an interesting time period and an important part of European art history. There was the industrialisation and creation of new treatment methods then (Monet is one of the first prominent people to get cataract removal surgery), and his role in impressionism and abstractionism in art. I also dove into his personal history, and his pretty rough life. Monet went to war, almost died of typhoid, amongst other rough times.

You mentioned TMP being set in an eyeball, but a lot of the elements in-game are heavily abstracted. What do they represent?

At the end of the 3rd level, that big monster is supposed to represent a typhoid. I don’t think it looks like a typhoid at all, but it’s a weird abstracted representation of it. Most of the in-game assets are an underpinning of something related to the eye, but abstracted to varying degrees. The green vines and the landscape that you run on are supposed to be the muscle strands and sinews of a green iris. The bad guys are perhaps bacteria or viruses. I pictured the balls that roll around to be blood cells or white blood cells.

More importantly, I wanted to explore the iris or barrier in the eye, the halfway point between the real world and the internal world. Like, what Monet would be thinking, what he would be feeling, in an abstracted layer away from reality. So that resulted in a really weird, abstracted, surreal world, with some areas drawing from real life.

So, is Monet’s eye colour actually green?

Originally, I think my first sketches were blue because I was thinking of a blue eye, and it was really intense to play because everything was really bright. Then I thought green would look more natural and understandable as a setting to people.

I later found out Monet’s eyes were brown and I went: “You can’t make a whole game muddy brown! It’s going to be gross!” Creative choices had to be made!

What’s the rationale for having so little UI in game?

For The Master Pupil’s puzzles, their mechanics are taught in a way that’s intuitive. If you need to explain to someone a story or a mechanic, the opportunity for one of those important “Aha!” puzzle moments have just been deleted.

From the very beginning, players find that the path forward is blocked by an enemy covered in spikes. A little platform exists right above him. The enemy looks mean, so it’s clear that to make progress, players have to run and then jump away from it. Those are the only usable inputs for the whole game, and it’s informed by practice rather than by any popup.

For the rest of the game, it becomes clear that players have to run and interact with things to feedback in a way that teaches them how to do the puzzle. Physical objects work really well for that: If you have a ball, it’ll roll. If you have a door, people understand the door can open.

In TMP, you have this red sniffy thing that will sniff you.

The reason I made the doors look like big, sniffy monsters was because I wanted a way for the ‘door’ to reject you. You can’t run up against it and try to jump over it because it’ll sniff you, and then sneeze you out of the way. So, in the early puzzles, the solution to get through the door right was right next to it: As you were blown away, you would be pushed into the red smoke, something people usually avoid because it’s red and a bit spooky.

Instead of explaining: “Hey, this is a red door. You need to be red to enter this room.”, just let players figure out what to do.

I played Braid, which had abstract stories and puzzles, but also giant chunks of text that made you pause in your journey to read. Then I played Limbo and Journey, which I was very inspired by. Both didn’t tell much literally. For Limbo, the name of the game tells you where you are, but that’s as much textual storytelling you’d get. Journey has sections that describe the story, but it is more about your emotions as you play and how you interact with the whole level.

I wanted to have an abstract story that told itself for TMP, with puzzles well integrated into it, showing instead of telling.

Lastly, the most practical thing was that no UI meant no need for language localisation. So, this game becomes accessible to any country, any person. You just need to experience it. That’s very exciting as an indie developer because now suddenly everyone can play my game rather than just a small subset of English speakers!

It’s said that impressionism led to the practice of plen-air painting, or painting outdoors. Did you ever do that for TMP?

I did, actually. Years ago when I started painting, I was out on this recliner chair with an art board and a canvas set up on it. I was painting out in the courtyard with all these plants around me, and had a friend snap a photo of me.

But outdoor painting is just a hassle, especially if you’re painting thousands of assets for a game! I did it a couple of times and then I was like: “This is hard enough, I’ll leave it to the Masters.”

What’s your biggest takeaway from developing TMP that you think fellow developers might find useful?

I think it’s marketing, that’s the hardest bit. Because it’s fun to make, design and build a game. It has its challenges, but even those are fun because you’re pulling apart a puzzle and putting it back together to make a toy that is fun to play, and a story that is interesting to you.

Marketing is this completely different beast, and may be difficult if you’re not used to it. I’d recommend recording what you’re doing and putting it away in a little library. When you’re building your game, make little clips, label them really well, and put them in a gallery. Because, a year before you’re going to end your project, you’re going to want to ramp up your social posts. You’ll want to have how-to videos and little documentary videos, or even funny bugs and little glitches. Build a library of assets ready to go.

The second point, which is in a way a bit depressing, is to be careful what kind of game you make. The way the market sways will determine how popular your game will be. When I started making TMP ten years ago, it was in a market that really liked Limbo and Braid, 2D puzzle games were popular. Now it’s all about games that are replayable or games that streamers will like to play because that’s how the majority of people hear about new games.

I think having an ear to the ground about what is popular, how games are being played, and how people are finding games is super, super important.

If you can make a game, make a game that people are interested in. I can make a very interesting game, but it doesn’t necessarily find its audience because there is a certain way that popular games are being found. It’s got a lot to do with how the Internet works in 2023. So I think there is a balance between adapting your game to a wider audience and a game you want to make.

Lastly, I think researching a lot of that stuff while you’re making games instead of coming up against it at the very end is important. Most of development comes up at the very start, but you do have to do a lot of marketing work throughout.

Thanks for reading! The Master’s Pupil is coming mid 2023. To support Pat’s upcoming game, be sure to: